Get Today in Masonic History into your Inbox. Sign up today for one of our email lists!

Need an article for your Trestleboard/Newsletter see our Use Policy

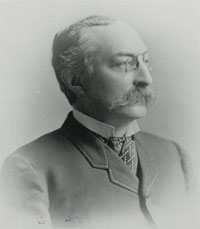

Garrick Mallery Passes Away

Today in Masonic History Garrick Mallery passes away in 1894.

Garrick Mallery was an American ethnologist.

Mallery was born on April 25th, 1831 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Mallery received an education largely from private tutors until 1846 when he enrolled in Yale College. He graduated from Yale in 1850. Three years later, in 1853, he received a Bachelor of Laws degree from the University of Pennsylvania. The same year he was admitted to the bar in Pennsylvania and began practicing law. Mallery was gaining a reputation in the legal profession until the American Civil War started.

In the Civil War, Mallery enlisted as a volunteer first-lieutenant in the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry. In June of 1862, he was wounded at the Seven Days Battles. He was unable to move and was left on the battlefield where he was captured by Confederate soliders. Some time later he was part of a prisoner exchange. After his release, Mallery returned home to Pennsylvania to recover from his wounds. In 1863, he was commissioned as a lieutenant-colonel of the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry. The 13th was assigned to Virginia during the military occupation of the state. He was appointed as the judge advocate of the First Military District. He left the volunteer service in 1866 and immediately was commissioned in the Regular Army as a captain. He received a promotion to brevet colonel for meritorious service during the Civil War.

In 1870, Mallery was assigned to the Signal Corps. He was part of the signal corps for almost 10 years, partially in the Dakota Territory. There he first saw the indigenous people speaking with signs and gestures. He also discovered pictographs on rocks, skins and bark. He made a large number of transcriptions and foresaw the loss of the knowledge as native tribes were brought under the control of the civil authorities. Before Mallery began his study of the pictographs they were believed to be per-Columbian, an origin with little or no meaning. Eventually he came to realize they, along with the hand gestures, were a complete system involving mythology and history. He also realized they were important to the spoken language as well.

When Mallery retired from the Army in 1879, his former commanding officer arranged to have him appointed to the newly formed Bureau of American Ethnology, whose purpose was to transfer records, archives and materials relating to the Indian of North America from the Department of the Interior to the Smithsonian. In the position he wrote several reports which turned into volumes, relating to the gesture language of various Indian cultures. His largest was 807 quarto (a single sheet of paper with four pages printed on front and back) paged report called Picture-writing of the American Indians. The report also contained 1,290 figures. Up to the time of his passing he was working on a follow on report, unfortunately he passed away before he could finish it. At least one of his reports is now considered the first authoritative exposition in the field of Ethnology, a branch of Anthropology which studies and compares different people and their relationship to each other.

One of Mallery's essays was Israelite and Indian. In the essay he compared the two cultures. At the time it was published it stirred up serious controversy.

Mallery passed away on October 24th, 1894.

Mallery was a member of Columbia Lodge No. 91 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

This article provided by Brother Eric C. Steele.